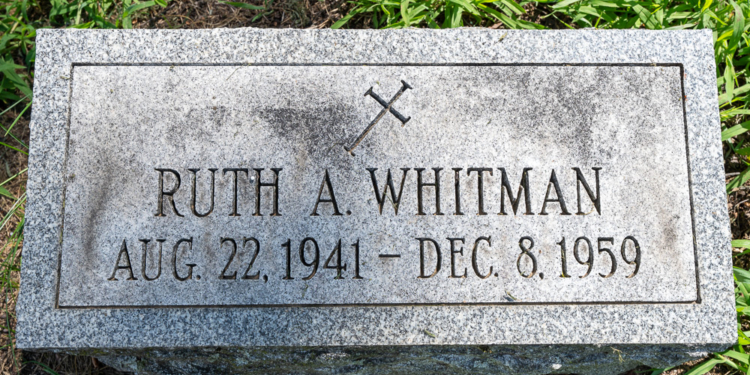

COLONIE — In what is considered a last-ditch effort to conclude the investigation into a nearly 63-year-old murder, police will exhume the body of an 18-year-old victim with the hopes of obtaining DNA that will lead them to her killer.

Finding evidence implicating someone for the December, 1959 murder of Ruth Whitman, though, is an admitted longshot.

“This was an investigative step we had always considered and it is certainly a drastic measure, in any case, to exhume a body, but at this point in the investigation there is nothing left for us to do,” said Deputy Chief Robert Winn. “This is the last attempt for us to try and get DNA evidence.”

Jim Franco Spotlight News

If there is DNA found on Whitman, it will be compared to DNA either secured by suspects who are still living or, if the suspects are dead, from family members who are still alive, including the brother and son of Robert Garrow, the Capital District’s most notorious serial killer.

All the original physical evidence collected by the State Police and Albany and Colonie police inexplicitly disappeared when the State Police moved their lab from Colonie to Albany sometime in the 1970s. There are volumes of written reports about the incident, and transcripts of interviews with a host of suspects, but advances in DNA technology cannot apply to those.

The written reports, said the relatively new lead investigator on the case, Colonie Sgt. John Santorio, indicate skin scrapings were found and collected from under Whitman’s fingernails, presumably the result of a struggle she had with her killer. He was intrigued, and applied for a $10,000 grant from the Season of Justice, a non-profit based in Indiana that helps fund law enforcement investigate cold cases.

Season of Justice has awarded more than $633,000 to assist police in 84 cold cases. It was founded by a retired Indianapolis police officer, Steve DuBois, and provides grants to law enforcement for advanced DNA analysis like forensic genealogy and next-generation sequencing.

Jim Franco Spotlight News

The Colonie Town Board recently voted to accept the grant and police have secured permission to exhume the body from Whitman’s family, the District Attorney’s Office, Cavalry Cemetery in Glenmont where she is interred and the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany. The last step is getting an Albany County judge to sign off on the request but, with everyone else is on board, investigators do not foresee an issue. When the exhumation will take place is still up in the air, said Colonie Lt. Daniel Belles, but it is expected to happen this summer.

“Nobody wants to do this. Nobody wants to disrupt a body but it is the last chance we have to bring closure to this case for the family,” Belles said.

If scrapings are found, they will be sent to a lab in Virginia. First it will check the results against DNA profiles already in the system. If it proves to be not that simple, the department has secured DNA samples from a host of suspects and/or members their respective families.

“For example, Robert Garrow’s brother is living and so is his son. So if there is DNA recovered from Ruth, a comparison to a brother or a son would be a strong indication and would be pretty specific,” Santorio said, adding both the son and brother have voluntarily given DNA samples.

While Garrow is just one suspect among many, Santorio said the exhumation could benefit the investigation into his potential involvement in other ways, too.

Whitman was beaten with a blunt instrument and dumped along Sand Creek Road, which at the time was desolate and seen as a convenient place to dispose of a body. Garrow was known to carry a specific type hunting knife, and used that knife in the commission of his other, litany of crimes. The original knife disappeared over the years — believed to be in the possession of a collector — but investigators found the exact make and model on eBay. The plan is to make a mold of Whitman’s wound and compare it to the handle of the knife to see if it is match. Measurements and photos of the wound were taken at the time, but they are not as precise as what today’s technology will produce, Santorio said. Also, according to written reports, Whitman had other injuries on her head and face and today’s technology could provide clues to her killer that were unavailable in 1959.

“There are countless suspects to name. There are several that evidence equally suggests they have been involved but there is no definitive conclusions that have been drawn,” Santorio said.

Another top suspect, Nelson Paul, Whitman’s finance at the time of her death, is still alive and volunteered a DNA sample. He had an alibi at the time of Whitman’s death, but was exonerated by investigators in 1959. He recently spoke with now-retired Colonie Investigator Kevin Terry via Zoom from his home in Canada because he is still considered a suspect given he was engaged to Whitman, was known to drink heavily and was convicted of killing a man in Canada — where he is from moved back to after Whitman’s death — and spent 20 years in prison.

“Even though the notes in the file appear investigators cleared him back then, and he has been cooperative to this point still today, and he offered his DNA sample which we secured we can possibly rule him in or out at the end of the day if there is recoverable DNA from the gravesite,” Winn said.

Exhumation

It is not as simple as just breaking out the backhoe and digging up a grave. Nobody currently working at the Colonie Police Department can remember ever having done an exhumation as part of an investigation, or for any other reason.

The body has been interred since 1959, so nobody is certain if the exhumation will yield any evidence or if, through the natural course of things, anything that could be potentially beneficial was slowly destroyed.

“The best experts we have consulted say that if the body was preserved in the way they preserved bodies at that time there is a chance we can recover something. They tell us this is not a wild goose chase,” Winn said. “If they said to us ‘you won’t be able to find anything,’ or if her burial site was in a spot that is conducive to water damage or storm damage or rot it may not be worth it to exhume her. But in this case we have a shot. If it is still there, we have a chance of recovering something.”

Jim Franco Spotlight News

If DNA is recovered, it will take between 16 and 24 weeks to process. While the cost of the DNA analysis is paid for by the Season of Justice grant, the exhumation will cost between $1,500 to $3,000, which Winn said will come out of the department’s drug forfeiture money.

DNA has a half-life of centuries, and if the physical evidence was preserved, like it would have been today, the exhumation would not be necessary. But, after an exhaustive search of the Colonie and Albany police departments, the DA’s office and the State Police lab, if there is one firm determination in this case it is that the evidence is gone.

Once the judge does sign off, the crypt and coffin will need to be carefully removed and there is a medical examiner on board to secure the DNA, if there is any to be had, and make a mold of the wound to Whitman’s head and analyze her other wounds.

Once the examination is complete, Whitman will be re-interred in a ceremony performed by the Catholic Church.

A bit of history

The plot of any book worth reading takes the reader up a hill and peaks when the prince saves the damsel or the hero slays the dragon.

To date, this story is still on the incline, and has been since Dec. 8, 1959, when a bus driver making his rounds spotted the body of Whitman face down in a water-filled ditch on Sand Creek Road between South Family Drive and Hunting Road. She had been beaten, but the official cause of death is asphyxiation by drowning.

Despite reports of her being a prostitute, police now believe she was a mild-mannered woman from a solid family who worked at the Albany County Nursing Home, when it was in the City of Albany, and made extra money as a babysitter. She had numerous friends in the colorful neighborhood, including those who used to hang out on Green Street, Albany’s red light district.

It took the family, and her fiancé, by surprise was when the autopsy on her body found she was between four and six weeks pregnant. At that early stage, she may not even have known, according to police. It may be more accepted now, but in 1959, a unwed, Catholic 18-year-old who was pregnant could be, in the eyes of some, considered scandalous.

She was last seen on Dec. 7, 1959, according to a number of witnesses interviewed by a number of police investigators over the years, at a large fire on Lancaster Street near the apartment she shared with her fiancé Paul.

Jim Franco Spotlight News

Everyone agrees, and historical accounts concur, the fire was a large spectacle that brought out the neighborhood and other onlookers. Investigators believe Whitman was at the fire, but who she was with, or where she went after, is very much an open debate.

Some witnesses say they saw Whitman at the fire and walk home alone. Others say she was with a yet to be identified man. Some say the there was nothing unusual about the two of them checking out what was a huge blaze with the rest of the neighborhood and some say the two were arguing. One witness claims the man punched her in the face, forced her in a car and drove off.

One witness says Whitman was supposed to meet a man who had an eye for her at a friend’s house but she never showed.

Two State Police troopers claim to have seen Whitman in the Morris Dinner on New Scotland Avenue at around 1:15 a.m. on Dec. 8 with a man in his 20s who they could not identify.

A Colonie resident claims to have seen a vehicle parked on Sand Creek Road at about 11:40 p.m. on Dec. 7 with two people inside sitting close together. Despite widespread publicity, the car and the other person — if there was a car and another person — were never located.

One indisputable fact is sometime that night, she was beaten and dumped along Sand Creek Road to drown in a ditch.

At the time, the Colonie Police Department was relatively new and very small so it relied on the State Police for assistance in most major cases and this was no exception. Since she was from Albany and last seen there, the Albany Police Department was also involved as was the Albany County District Attorney’s Office. Over the years, hundreds of pages of interviews and/or interrogations, have been accumulated by the four agencies. Student at the College of St. Rose Cold Case Analysis Center have assisted Colonie police in compiling the volumes of data.

There are a number of prime suspects, each with a near equal evidence implicating them as the killer. Some who were exonerated by past investigators might still be guilty of the crime.

“There are 300 pages of suspects from the Albany police, the State Police and the Colonie PD and a lot of these people were never ruled out or conclusively implicated. They did what they could at the time, but without DNA testing, it was nearly impossible to conclusively determine if someone was responsible or not responsible,” Santorio said. “For example, at the time, they relied heavily on lie detector tests, which turned out to be not reliable by modern day law enforcement standards, so some of those suspects who were ruled out, based on lie detectors, are still suspects.”

Paul remains a suspect because of who he was to Whitman, the fact he claims he did not know she was pregnant and his drinking and criminal history. His alibi was near airtight on Dec. 7, 1959, though, because he was working at the White Tower restaurant on Pearl Street, and every time investigators talked to him over the years he was forthright and cooperative. Most recently, the now 82-year-old volunteered a DNA sample, which the Royal Canadian Mounted Police secured and shipped to Colonie. He begged Colonie police to find his young lovers killer.

“Garrow was interviewed 2.5 years later by the Albany County DA at the time. He denied knowing Ruth and claimed he was never in Colonie, which proved to be a lie since he was working for an electrical company in Colonie,” Santorio said. “Some of his answers were evasive. For example he was asked ‘did you kill Ruth Whitman,?’ And he would say ‘I don’t know Ruth Whitman’ rather than say ‘I didn’t kill anyone.’”

It is not clear when Garrow moved to the Lancaster Street neighborhood but at the time of Ruth’s murder he had already had some run ins with the law and in 1961 he was arrested for a brutal attack on two teens — he assaulted the male and raped the female. Some 14 years later, he admitted to killing four people over an 18-day period and was sentenced to prison. In 1978, he attempted to escape and was shot dead by corrections officers.

His brother and his son have agreed to give DNA samples.

Also, there are records of an interview between Garrow and his psychiatrist that are still sealed. Santorio said he believes he has maneuvered the legal obstacles and will soon get a chance to read the entire file. While the psychiatrists report is public, the notes used to compile the report are still sealed and he hopes there is an off-the-record mention of Whitman — or at least a woman in Albany — included in the notes.

“He was an admitted serial killer living in the same neighborhood and was potentially with Whitman at the scene of the fire on the night of the murder,” Santorio said. “How can’t he still be a suspect?”

Another suspect died in a car accident and had a scratch on his face shortly after Whitman’s body was found. He claimed it was from a cat, but a number of witnesses say he never have a cat. He was also suspected of murdering his two children, but charges were never brought.

Jim FrancoSpotlight News

Another suspect was married to one of Whitman’s sisters and was said to have had an eye for his wife’s sibling. Police also caught him attempting to solicit sex from underage women in the Lancaster Street neighborhood.

Whitman also once dated a man from Canada, who took one of her friends to the same area of Sand Creek Road and attempted to sexually assault her before dumping her out of the car. He is still alive and in his 80s. Investigators working the case today have not talked to him as of yet but it is imminent.

“Having suspects in this case is not a problem. Having something that eliminates them or makes you focus on them is the problem,” Winn said. “There was an incredible amount of police work done on this back then but unfortunately none of it had a conclusion.”

Why?

As the years tick by, fewer and fewer people with first-hand knowledge of the case and/or of Whitman are still around. The Lancaster Street neighborhood Whitman and nearly all the suspects and witnesses called home was decades ago bulldozed to make way for what is now the Empire State Plaza.

She does, though, have three sisters, of 10 siblings, who are still alive including her twin and there are a number of nieces and nephews. Police said the family did not want to talk to the press at this point in time because of how she was portrayed in the past.

Police spent countless hours on the case in 1959 and 1960, and while it was never officially closed it was re-opened again in 1970 and put on a shelf until 1993 when a new, ultimately unfounded lead took investigators to Missouri. It was revisited in earnest in 2012, again in 2019 and now in 2022 with the planned exhumation.

For police it is a once-in-a-career chance to advance, and potentially solve, a fascinating cold case.

“It is refreshing. It is different from the same old modern day cases with bail reform and changes in the state Criminal Procedure Laws that have, I would say, been demoralizing to see them just release people we arrest so they can commit additional crimes,” Santorio said. “This has taken my attention away from all that and focus on a really interesting case and hopefully we will get luck and get some resolution for the family.”

Winn agreed.

“You want to get justice for the victim and you want to get answers for the family and you want to have a conclusion. You think in your mind, as officers or investigators, it will help the family. You would think they have moved on by now but they still want to know,” Winn said. “We are naturally curios and inquisitive people who want to help. You don’t want things to be unknown. It bothers normal people, but people who take this job, police officers and investigators, you want to have an end. Sometimes it is not the end you want to have but you want an end because there is always the ‘what if’ if you don’t have an answer at the end.”