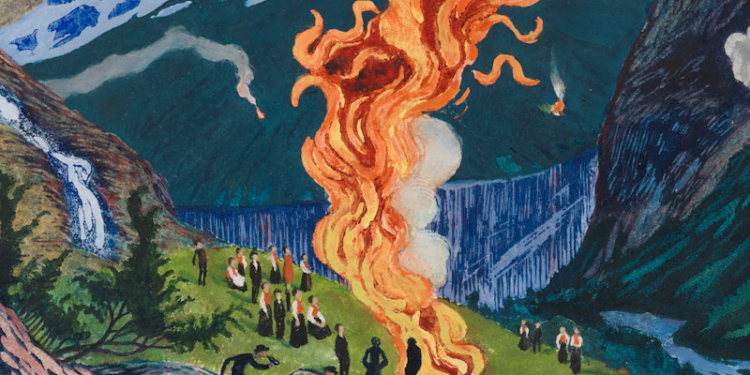

When I visited the Clark Art Institute in early June, the monthly pamphlet had a stunning print on the front entitled “Midsummer Eve Bonfire.” I remember pausing on the image, thinking how breathtaking the scene and colors were, even on a glossy sheet of informational material. Had I simply opened the pages of the pamphlet, I would have learned the name of the artist. But it wasn’t until a few weeks later that I stumbled upon it.

Nikolai Astrup. A 20th century Norwegian expressionist, Astrup is a name that few outside Norway are familiar with. In fact, the Clark’s exhibition “Visions of Norway” is the first retrospective of his work in North America.

MaryAnne Stevens is guest curating the exhibition and has been working for several years to push Astrup’s name into international arts circles. Stevens is an art historian by training and was the Director of Academic Affairs for the Royal Academy of Art in London. Now, she is an independent scholar and curator.

As a part of her efforts to educate the art community about Astrup, she presented at a conference in 2017 that was focused on artists’ homes and gardens. It was there that the Clark’s Director of Exhibitions and Collections and Curator of Decorative Arts, Kathleen Morris, was in attendance, and where she had her own experience of hearing the name Nikolai Astrup for the first time.

The artist grabbed Morris’ attention for several reasons. The first and foremost, based on the nature of the conference, was his fascinating and early commitment to sustainability and conservation of both land and architecture.

Astrup built and maintained his own farmstead called Sandalstrand overlooking Lake Jølster, which doubled as a studio and source of inspiration for his work. His art preserved nature indefinitely, but it was his work on the farmstead that preserved nature as he lived until 1928.

It is quite fitting that Astrup’s art — though he grew up Lutheran — plays upon the magical realism of Norse mythology. As a religion rooted in Paganism, nature is given a spirit, a belief that is made apparent in Astrup’s beaming landscapes that he paints as expressions of life and enchantment.

His painting “A Morning in March” depicts a mountainscape partially concealed by a tree and its branches. But it is the trunk of the tree, the body, that is given subhuman features. It has two branches wider than all the rest that transform to hands as they extend upwards. Surrounded by snow, the tree should seemingly be bare from the harsh winter elements. But the buds at the tips of the branches and the patches of grass surrounding the tree’s base suggest prevailing life.

The Clark, sitting on 140 acres of land in the Berkshires amongst meadows, trails, and mountainous views, is the perfect location for Astrup’s North American debut.

“There’s a lot of synergy between Astrup’s art and our collection and our location,” said Morris. “… We ourselves are on this beautiful large piece of land that we take care of and we ourselves are stewards of land in a similar way that he was. It’s a very important part of our identity and our mission.”

The figurative properties of Astrup’s work are expressed through his technique rather than through direct depictions, Stevens explained. As an expressionist, this is not atypical. But what makes Astrup great is his mastery of technique to create a mysticism that is so close to reality yet remains completely distant from it.

“You are so aware of the way in which he manipulates the surfaces of his paintings: great gestural brushwork, extraordinary range of colors…,” said Stevens. “At one point I was doing a count of the different words he uses to describe green, and I think it was about 12. From poison green, to moss green, to lichen green, you name it, it’s there. It’s that awareness of color which is very impressive.”

Astrup’s innovation in European printmaking is especially significant. He adopted the style of Japan’s ukiyo-e woodcuts. Whereas wood engravings were carved against the grain to show more detail, ukiyo-e carves along the grain for a design that “forces you into simplification of form and outline, so color becomes sort of blocked in rather being able to take on nuances of highlight or shadow,” as Stevens put it.

In Astrup’s prints and paintings, the influence of Japanese art is clear, even offering parallel motifs. Ancient Japanese art, for example, was very much affected by Shinto beliefs and rituals. Like the Paganism that Astrup depicted, Japanese art drew upon the naturalist spirits that existed in Shintoism. When looking at the artist’s prints like “A Night in June in the Garden” or “The Moon in May,” one will notice the beautiful simplicity that Stevens pointed out.

She later explained that, though their printmaking techniques were different, Astrup believed that “as far as innovation in modern printmaking is concerned, there is only Munch and him.”

Munch was the Norwegian expressionist who gained international acclaim, though he and Astrup created at similar times. The reason for Astrup’s confinement to Norway lies largely and simply within the bounds of accessibility. Nearly all the literature on the artist was strictly available in Norwegian, and all of his work, excluding one painting, was housed in Norway’s public or private collections.

It is an unfortunate lack of recognition that was the result of institutional limits rather than public disinterest. But the hope of Stevens and Morris is that as Astrup’s work spreads, people will learn his name and his story.

The exhibition runs from now to Sunday, Sept. 19. Visit clarkart.edu/astrup for more information.