BETHLEHEM — Skip Parsons continues to keep the spirit of Dixieland jazz alive.

The 80-year-old clarinetist is in his sixth decade of performing the style of music once popularized by the likes of Benny Goodman and Louis Armstrong. He and his group, the Riverboat Jazz Band, perform one weekend a month at The Fountain on New Scotland Avenue in Albany, and he is looking to perform a once-a-month show at The Twisted Vine at the Four Corners in Bethlehem with his other group, the Clarinet Marmalade Trio.

The Albany native and Feura Bush resident said his interest in Dixieland dates back to his childhood.

“When I was a kid, my aunt used to take care of me when my mother went to work. She used to get these records of Bing Crosby and Louis Armstrong and all that,” said Parsons. “I guess that was the start of it.”

At first, Parsons said he wanted to be a saxophone player like his cousin and another friend of his, but he was told to start with the clarinet. Once he picked up the clarinet, though, he never put it down.

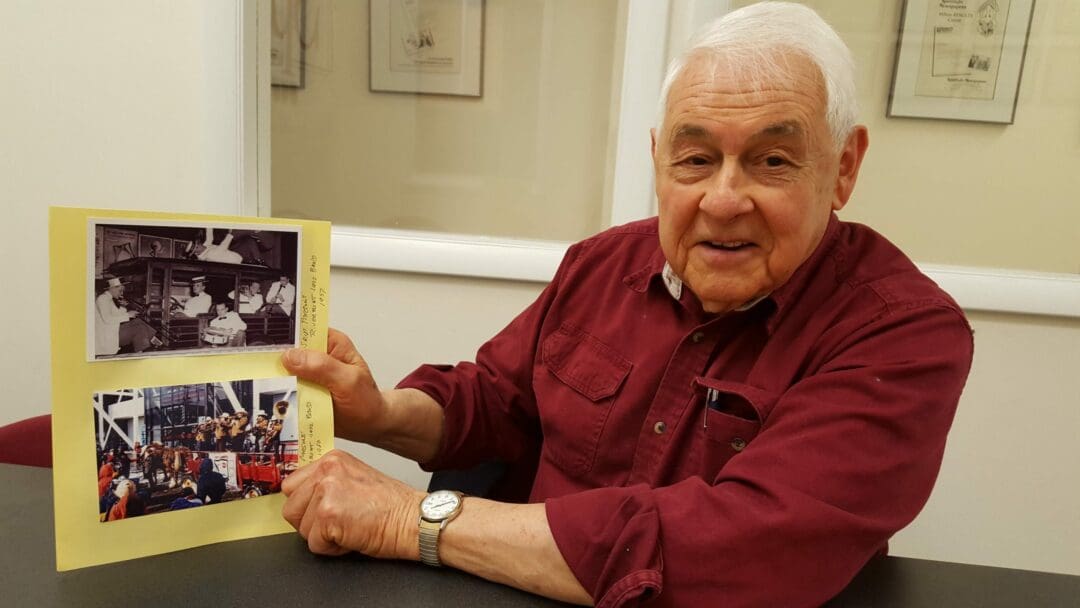

“I did eventually play the saxophone, but I found my greatest pleasure was playing the clarinet,” said Parsons. “It was much harder to play.”As a young man growing up in the big band era, Parsons wanted to emulate his musical heroes such as Goodman and Armstrong. With the help of his friend and drummer, Tom Brown, he formed his first group in 1955 and played shows at the Van Schoick Tavern in Cohoes. Eventually, the band grew into the first incarnation of the Riverboat Jazz Band in 1956.

Over the next 60 years, the Riverboat Jazz Band has had many members come and go — to the point where one of Parsons’ friends, Cliff Lamere, started a website dedicated to listing all of the people that have been part of the group.

“He’s got some pictures of people that he took or pictures that he got from me or other people that he has on the website,” said Parsons. “So, there’s been probably 250 people who have played with me.”

One of the few constants for Parsons has been his band’s monthly shows at The Fountain. For the last 45 years, the Riverboat Jazz Band has played the second weekend of every month at the venerable Albany restaurant — a deal he struck with his friend, John Romano, who founded The Fountain. The shows were a big hit with the locals, and Romano was just as much a part of it as the band, as he interjected comments and pretended to play a clarinet by holding a Galliano bottle while standing on the bar.

Romano died in March 1976, but the Riverboat Jazz Band’s monthly shows continued.

“John told his wife (Bonnie), ‘I want you to know that if anything ever happens to me, I want them to always have their job,’” recalled Parsons.

Parsons’ shows continue to draw crowds, especially as younger generations come into contact with his style of Dixieland jazz.

“It’s wonderful, and some of it came around with the business of the swing dancing,” said Parsons. “We used to play some of those things, but those kids got to know us from some of that and they still come around.

“Some younger kids … can appreciate what we’re doing, and they appreciate the talent and they like the music. I’ve been known to say, this is about the third time in my life the kids came around again — and they’re coming around again now, which is marvelous. But, it’s not really their music like it was the music of people my age. The music of their age is not us, although they can appreciate us and they like us. It’s not their thing.”

Playing music has brought Parsons to some interesting places in his life. He’s had the chance to play with some jazz luminaries such as Jimmy McPartland, John “Ed” Hubble, Bobby Hackett and Vince Giordano. He and his band once played for former New York Governor Mario Cuomo.

And then, there was the time Parsons and his band became ABC’s official band for its 1980 Winter Olympics broadcasts from Lake Placid. For nearly two weeks, they played at several venues around the village, and even got the chance to kick off the first broadcast from the top of Whiteface Mountain.

As Parsons recalled, the band wasn’t even fully assembled when the request came in from the network producer.

“We couldn’t get everybody up there because of the credentials and the security and all that stuff,” said Parsons. “So it’s 11 o’clock at night and I’m in … Marvin Bayer’s office, and he was the chief honcho there. And he said, ‘We’re going to have you up there to start the Olympics up on Whiteface Mountain tomorrow morning at 7 o’clock.’ And I said to him, ‘We’ve got a problem. I only have three of us here. We still got three more guys down in the Albany area.’ He said, ‘Who are they?’ I give him a name, he said ‘What’s his address?’ And there’s a guy walking by the door. He says, ‘Hey Sam’ — or whatever he called him — ‘take this over to George and send a bus down to Albany to pick these guys up.’ Just like that, they went down in the middle of the night, picked those other three people up, and the next morning we were on Whiteface Mountain.”

The original plan had the Riverboat Jazz Band performing on a horse-drawn flat bed stage, but it was nixed when the police told them everyone needed credentials — including the horses.

“So, the broadcast people said to me, ‘We’ve got another plan.’ They put us on this (tractor), went to the top of Whiteface Mountain, and that’s where we started the Olympics — in the snow,” said Parsons. “We set up to play … the women’s downhill was supposed to be first. And we became the first thing on documentary tape in the Smithsonian Institute. They had across the front of Ernie’s tuba ‘1980 Winter Olympic Games, Lake Placid, New York.’ And they backed up, and there’s the band. And then they moved over to the women’s downhill.

“Stuff like that happened every day. Every day, something … just a miracle thing.”

And speaking of miracles, the Riverboat Jazz Band found itself in the middle of a wild celebration after the United States defeated the Soviet Union 4-3 in the “Miracle on Ice” hockey game.

“We were ready to leave (on the day the U.S. hockey team beat the Soviets) … and I get this phone call,” said Parsons. “Ed Lewi, who arranged that whole thing for us, was on the phone. He said, ‘Oh, you’re still here,’ and I said yeah. ‘Have you got a band?’ And I said, ‘I think so. We’re packing up.’ ‘Get down to the Olympic Arena. We might win the game.’ So we got down there, but it was so crowded that we couldn’t get in.

“So, we’re outside. I said, ‘Let’s stick it here for a little while. Maybe somebody will come around.’ And then all of a sudden, the doors flew open and they (the fans) come screaming. And I thought, well they must have won. Anyway, they came over and they tried to pick up Ernie (Belanger) with his sousaphone … and this was all on the front page of the New York Post the next day.”

Parsons hasn’t been part of any wild celebrations since that day in 1980, but he still feels the rush of playing Dixieland jazz wherever he goes.

“It’s forever changing; it’s forever new,” said Parsons. “With jazz, you’re never playing the same thing twice. You’re playing the same song, but you don’t play the same licks. You’re always reaching for new statements or new notes to play, and you’re always working on it. It’s a challenge.”