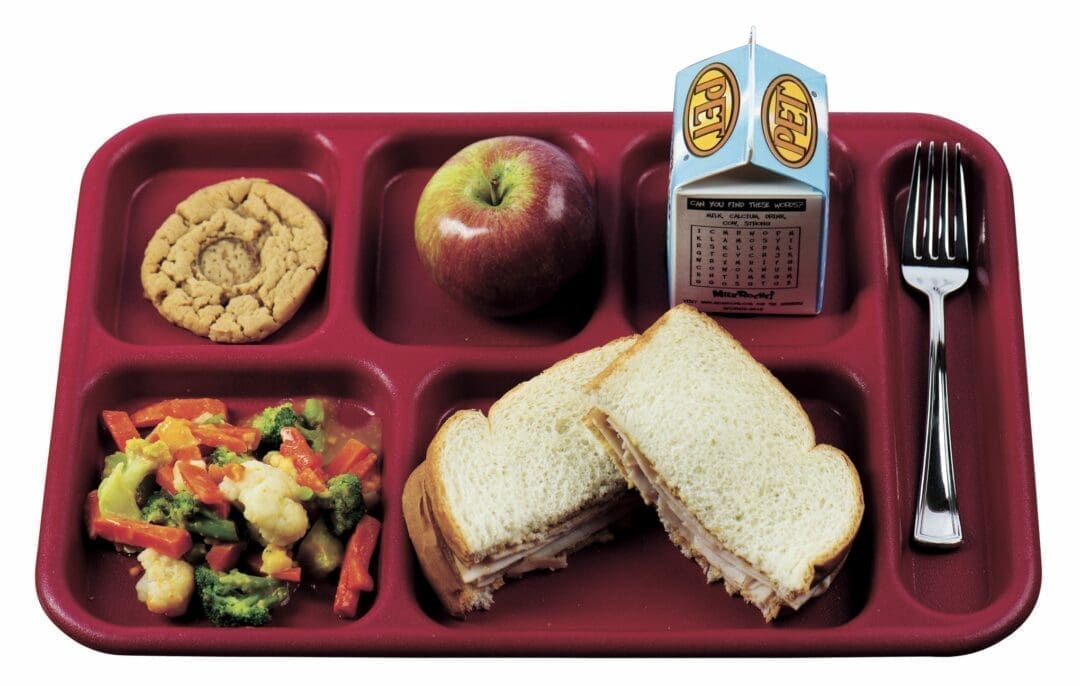

Students still have a few days before the morning bell chimes again, but schools have already been hard at work in the kitchen preparing to feed pupils. School districts throughout Schenectady County are preparing to offer a slightly different fare to students at breakfast and lunch after new federal food service regulations were implemented in July. The new regulations are based on recommendations from the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies and are “expected to enhance the diet and health of school children and help mitigate the childhood obesity threat,” according to the USDA. Kimberly Gagnon, supervisor of the Food Service Program at Mohonasen Central School District, said the guidelines wouldn’t only be beneficial for kids. “Overall I think it is a very, very healthy way to eat. If we all followed these guidelines none of us would have these weight problems,” Gagnon said. “I think that we are a society where the portions that are served are way, way too big.” In 2010, President Barack Obama signed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, which increased the number of children eligible to participate in free school lunch programs and required school districts to be audited to improve compliance every three years. It also set new nutritional standards for all foods sold in schools. The new rules require schools to increase the servings of fruits, vegetables, whole grains and fat-free milks. The amounts of sodium, trans fat and saturated fat allowed in foods have been reduced. Meals must now meet caloric limits based on the age and grade of students, too. Under the new regulations, fruits and vegetables can have no added sugars or syrups and must be either fresh or frozen, with limited use of canned produce allowed. A limit is also placed on the number or times starchy or deep-fried vegetables can be served each week. “The goal is to help children make better choices on what they are eating every day,” Marcy vonMaucher, director of Food Services for Schalmont Central School District, said. “If you start in school they can take it home with them and encourage their families to adopt the my plate goals.” School districts knew changes were coming and many have been implementing their own changes to offer more vegetables and fruit options and ease students into dietary changes. “Our program already included lots of fruits and vegetables,” Robert Hanlon, spokesman for Scotia-Glenville Central School District, said. “We will meet all of these obligations.” Scotia-Glenville food services are contracted out to Chartwells, but the district’s bid requirements for the service require the company to follow guidelines of the school’s Wellness Policy. In addition to nutrition standards, the policy focuses one physical activity, nutrition education and wellness activities. “Because we deal with a private entity we made sure that was part of their bid,” Hanlon said. Scotia-Glenville’s food offerings already incorporate elements of the new guidelines, but Hanlon said there would likely be “some tinkering” with what is offered. The most exciting aspect to vonMaucher is the new guidelines are brining about a nationwide change in what schools are serving children. She has already talked to people from across the country, including California and Oregon. “It is encouraging everybody around the nation is going to be doing the same thing,” she said. Local districts appear to be receptive of the changes, but how students will react to a new menu is unknown. “For me, the challenge has been to find fruits and vegetables that I know kids will eat and fit into that calorie quota,” Gagnon said. “On paper … it doesn’t look terribly different, however when the kids go through the line they are going to notice the difference.” Hanlon said students will notice larger portions of fruits and vegetables and smaller portions of “things that are not good for them.” Portions sizes will also be smaller than before, too. “Now they can’t have cheeseburgers every day,” Gagnon said.

Cheeseburgers will likely become a rarity, because Gagnon said it is difficult to serve meat and cheese on the same day under the new guidelines. Hamburgers would also be served on whole-wheat buns. She used to make salads with shredded cheese and some type of meat, but at the elementary level that would be tricky to do while still meeting the guidelines. And while the quantity of chicken nuggets served won’t change, the nugget itself will be different. Processed meat was common before, but now the nuggets will be low-sodium, low-fat, white chicken breast meat and breaded with whole-wheat grains. “Even though they are getting the same chicken nuggets, it is a different chicken nugget,” she said. “We have been making the changes gradually, so I am hoping the kids here are not completely thrown off.” At Schalmont, vonMaucher said one of the first changes was moving from a white hamburger bun to whole grain and likewise for hot dog rolls. “In the beginning the children looked at them differently … but over time they began to accept them,” vonMaucher said. “The more they see it the more it becomes commonplace to see it and it isn’t different anymore and they accept it.” She said the hardest part is just getting kids to try something new. When the school first started serving refried beans, she said perhaps 10 percent of the kids put it on their plate. Now, half of the students will take refried beans. At Schalmont, vonMaucher said two thirds of the students purchase lunch at school and about 15 percent of students are approved for the free or reduced lunch price program. “We’re pretty low on that scale, so it is a positive thing when the kids are still buying lunch and your partition is still up when you are not a high free and reduced area,” she said. Mohonasen has a similar amount of students purchasing lunch at about 60 percent, Gagnon said, and about 30 percent of students qualify for free or reduced lunches. Gagnon said while the new guidelines would be an adjustment for students, some of her staff will have to adjust to it, too. “I think they come from a generation of more food is more love, so I have to make them understand that by providing portions that meet the guidelines in the long run we may be savings some of the kids from obesity,” she said. “They can’t equate love and food.” The Mohonasen Food Service Department noticed many elementary students were purchasing second entrees with their full lunch and recently changed the district’s guidelines to require parents to give permission for such purchases. Mohonasen’s concern wasn’t centered on providing the additional food, but rather the cost to parents. District officials said many students purchasing a second entree were seen throwing out a large portion of the additional purchase. Scotia-Glenville has also noticed some elementary students purchasing two lunches. Hanlon said the district is looking to discourage kids from doing it without banning the practice. While kids in the lunch line will be noticing new options, parents will likely be made aware of new prices. All four of the school districts in The Spotlight’s coverage area will be increasing lunch and breakfast prices, from as little as a nickel to as much as 50 cents. In-house school food service programs are self-sustaining, so all expenses must be raised through revenue from purchases and state and federal reimbursements. Niskayuna Central School District is increasing all lunches by 50 cents, which is the first price increase since 2008. Elementary students will pay $2.75 and it increases along grade levels, with middle school students at $3 and high school students at $3.25. Staff lunches are $3.70, plus tax. Last school year, Niskayuna schools served more than 272,000 meals and held an operating deficit at the end of the year. District officials said the move to more fresh ingredients and cooking from scratch, alongside rising food prices, led to the gap. The district used its school lunch fund balance to make up the loss. Gagnon agreed the new guidelines are increasing the cost of lunches.

“The amount of produce that we have to purchase and the fact that every student has to take a fruit or vegetable is going to increase our produce cost tremendously,” she said. She said having to purchase fewer grains and protein items might help balance out the increased cost for produce. Whole-grain foods are more expensive than white bread, though. Staffing levels may also have to go up as staff spend more time on preparation.

“If anything, because we are trying to get back to more scratch cooking and to preparing fresh fruits … there could be an increase in staffing necessary to accommodate what foods need to be prepared for students,” vonMaucher said.Success hinges on students

The cost of change

Reporter Marcy Velte contributed to this story.

The new lunch line

Leave Comment