DELMAR — Hidden off the dead-end road is a time machine, as the suburbs melt into the quiet tranquility of Normans Kill Ravines Park on 70 Wright Lane. The park is on beloved ground for Delmar resident Olive Mae Wright Hallenbeck.

“People have no idea what that used to be back there,” said Hallenbeck. What are now biking trails and the inviting landscape of the new park were previously hay fields and the sprawling farmland that belonged to the Wright family’s 101 Acre Ranch.

The Wright family’s attachment to the property can be traced back to Walter Wright. Shortly after his marriage to Olive Tolhurst McNary in 1910, the newlyweds, along with his parents and siblings, moved to the farmland on North Street.

The 1913 Family Directory of Delmar records the two families living next door to each other. Since then, members of the Wright family have continued to live there for over 100 more years. Wright Lane would then be named after the family farm, a common practice of the era.

The history of street and place names is unique to every town. “In the 1900s, the name went along with who the property owner was,” explained Susan Leath, former Town of Bethlehem Historian and active Bethlehem Historical Association member.

“Often the street names were named after the people and the families that lived there. That’s one way to remember who the families are,” added Leath. With the passing of time and the creation of subdivisions, street names gradually have dwindled in their association with the original families that lived on them.

After turning eighteen, Hallenbeck left the farm when she married. However, her fond memories illuminate a vivid picture of her childhood spent at 101 Acre Ranch.

“The barns are what I’d like to have remembered,” she said. The property’s barns have since been demolished. The barns were multipurpose and essential to transitioning the farm through several stages of growth and the property’s evolution over the decades.

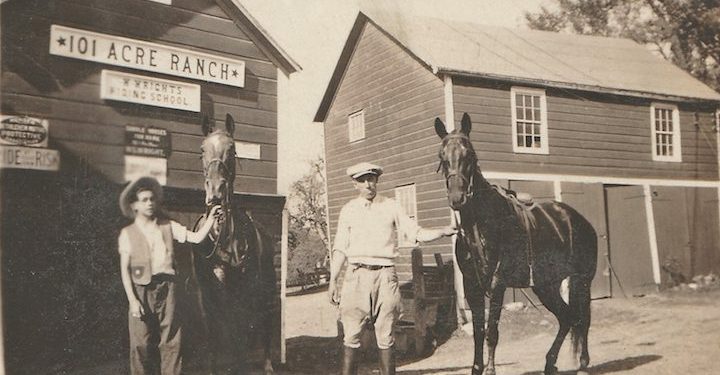

101 Acre Ranch boasts a rich equine history, dating to Walter Wright’s Riding School in the 1930s and early 1940s. Advertisements from the school praise Wright’s ‘exceptional’ horses and the benefits of horseback riding as an activity for everyone.

A favorite memory of Hallenbeck’s is spending time horseback riding. As a young girl growing up on the farm, Hallenbeck had a horse named Silver, named after The Lone Ranger.

“I could ride all the way out to the railroad track,” she said. Hallenbeck would ride Silver, where the Ravines biking trails now stretch out. “It didn’t look then like it does now,” she quipped.

Later, the farm became actively involved in the dairy business, with Hallenbeck recalling how “Grandpa Wright had dairy cows.”

“It was a lot of work to keep that place going,” she added. There were no snow plows; winters were difficult to combat at times and bred a sense of endurance. Tractors would help haul them out of snow banks on the road to the farm.

On a recent visit, Hallenbeck saw the newly paved road at Normans Kill Ravines Park. “Bethlehem has gone from a little quaint place to a beautiful town,” said Hallenbeck. “When I grew up, there were dirt roads. Back where the park was, it was almost like a secret because it was a dead-end road. Over all the years, it’s changed.”

Hallenbeck’s goal is for the park to commemorate the Wright Family’s heritage and for people to realize the land and that her family “lived there and made a living off that land.”

“I would like to bring awareness to what the land was,” said Hallenbeck, “and would like it to be recognized for the Wright Family.”