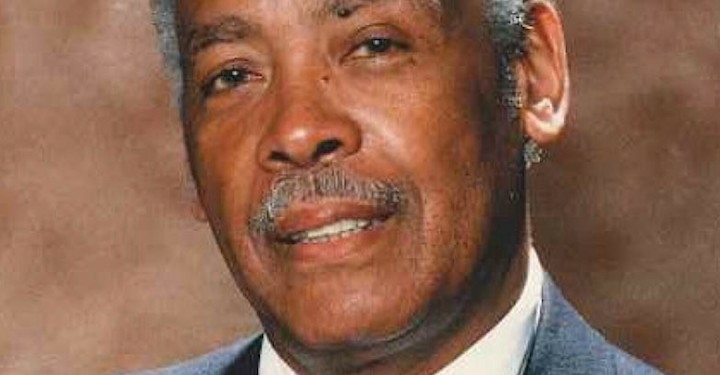

DELMAR- Peter Pryor, the civil rights attorney who traded in his soldier’s rifle for a law degree, leading the charge for racial equity from Albany courtrooms, died on Dr. Martin Luther King’s Day at the age of 95.

His years on this earth were spent fighting racial injustice with the use of the Constitution.

“I was going to fight what I had seen in this country and maybe elsewhere,” Pryor told Albany Law School’s Lisa Suto, in a recent podcast. “I said to myself, I don’t think I’m able to do this with an M1 rifle or driving a Sherman tank. Maybe the courts would be the best place to do it.”

Shortly after he was born, Pryor’s family moved from Savanah, Georgia to Daufuskie Island, a barrier island off the coast of South Carolina. His pre-school years were spent playing with the other children on the island in what he described in an Albany Law School podcast as an “idyllic place.”

His family lived within the Gullah community on Daufuskie Island for six years. The way of life was distinguished by a rich heritage that borrowed languages and folk beliefs from the Bahamas, Barbados, Guya, Belize, Jamaica and Sierra Leone as they lived excluded from white society.

“When I returned to Savanah, I was of school age. However, my mother had to keep me out of school for a period of time and I was home taught. I remained out of school simply because I didn’t speak English well, I spoke Gullah. … Sometimes my wife says I still carry what we call the Geechee accent.”

He was home taught by his father, who had him work on his English by listening to Gabriel Heatter’s accounts of the news on the radio. By the time Pryor was ready for junior high school, he had read “just about everything readable back and forth through the books of knowledge.”

He left home to enlist in the Army at the age of 14. After which he served overseas in the European campaign of World War II. Once he was discharged at 19, he moved in with his brother in Albany to attend college. He attended Siena College before enrolling at Albany Law School. In 1954, he earned the distinction of being the first African-American to graduate from Albany Law School since the Reconstruction era.

“Throughout his life, Peter fought for equity and inclusion. He was an inspiration for so many,” said Alicia Ouellette, President and Dean of Albany Law School. “I’m proud to have known him and we are proud to be able to count him as part of the Albany Law School family.”

Pryor became a prominent civic affairs leader. He served as a civil rights attorney and soon became a key figure in several high-profile discrimination cases.

In 1958, he successfully challenged the City of Albany in the case of Barbara Ann Sharpe, a 14-year-old African-American girl who was denied access to the public pools of the City of Albany. Sharpe filed a complaint with the State Commission Against Discrimination, claiming Ackley-Maynes Co. denied her entry into the popular Mid-City Swimming Pool on account of her being Black. The company was fined $400 and its manager, Henry G. Finn, was sentenced to five days in jail. The case was the first to result in a fine or jail sentence under the state’s anti-bias law, which at the time, was over a decade old.

Pryor represented Samuel Clark, a Black man who spent six days in the hospital after he was arrested on Memorial Day by Albany police for double parking on Jefferson Street in 1962. He spent six days in the hospital immediately after posting bail. He charged police of beating him while under custody. His public claim caused enough stir to force Mayor Erastus Corning to call for a grand jury investigation. In his 1977 book “Machine Politics: A Study of Albany’s O’Connells,” author Frank S. Robinson described the grand jury as a tool used to strong arm opponents of the Democratic political machine. Charges were never issued against the police that fall. They indited instead the Knickerbocker Press reporter who thoroughly covered Clark’s story leading up to the investigation.

As he fought in the courtroom, Pryor founded the Albany Urban League and was elected president and general counsel of the Albany chapter of the NAACP. He would later serve as an Assistant Attorney General and counsel to the New York State Pure Waters Authority, and later be appointed Chairman of the New York State Consumer Protection Board by Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller before returning to private practice in 1980.

Pryor represented Carole Riley in a publicized dispute with the Town of Bethlehem that garnered the attention of the New York Times in 1997. Riley, who was then the operator of nearly 50 area Pizza Hut restaurants, had moved into Slingerlands with the intent of running her businesses along with her seven employees from her $460,000 home. After she was cited with code violations related to operating a business in a residential zone, she sought a use variance.

“This is the first time I’ve been here in 30 years, when I enrolled my children in Delmar School,” Pryor said, greeting Town Board members from inside the former elementary school’s auditorium. “Since then, I see things have changed. And that is good, because that tells me we are not anchored down to the past.”

When she was denied, she filed a lawsuit totaling $15.25 million in damages. In the suit, she claimed the town refused the exception because she was a wealthy, black woman from Harlem. On the night of that decision, a suspicious fire destroyed several storefronts in a Delaware Avenue strip mall, including the only Pizza Hut in town. An investigation revealed the fire was ignited from the packaging and shipping business next door. A suspect was later arrested on arson charges. Riley’s lawsuit was dismissed nearly two years later.

Pryor would earn honorary distinction through the years, commemorating a exemplary career benefiting the community in which he served. His honors include having been named a trustee emeritus at Albany Law School and Siena College, and regent emeritus with the state Education Department In 2015, the Capital District Black and Hispanic Bar Association created the Peter M. Pryor Pioneer Award to honor his life and work. He was a recipient of both Albany Law School’s Distinguished Service Award, and with his wife Barbara J. Pryor, was awarded the Community Laureate award — one of the University at Albany Foundation’s highest honors.

In a joint statement Chancellor Lester W. Young, Jr. and State Education Commissioner Betty A. Rosa said after his death, “A giant in the New York civil rights movement, Regent Emeritus Peter M. Pryor was an unwavering pioneer in the fight against intolerance and injustice and a champion of education. He took on those in power, steadfastly advocated for the oppressed, and never wavered in his dedication to equal rights for all. …

“Many generations of New York’s children have benefited from his lifelong efforts for equity. We extend our deep condolences to Regent Emeritus Pryor’s wife, Barbara, his children, and all who loved him.”