What is the definition of success? That’s a loaded question.

Merriam-Webster recognizes the answer goes beyond what it says is a favorable or desired outcome. No. The book of words goes on to say it could mean the attainment of wealth, favor, or eminence.

Eminence.

There are plenty of emcees who’ll declare eminence over the fodder. Prove it by stepping into a cypher armed with a mic, a keen mind and a razor-sharp tongue. Whether on stage or in the booth, the best come out on top with flow. A manipulation of words, rhyme and music so smooth it would cause William Shakespeare to pause if the Bard stood in the crowd.

“When I was in high school, I wouldn’t have pictured myself in the position that I’m in,” said Jake Strain from his perch at Off The Road Media. The recording studio sits over the basketball court in the Washington Avenue Armory. He’s there today to be interviewed. Taking a quick moment before he runs off to an engagement shoot with his fiancée, Nichole. She’s expecting their second child (who has since arrived). “I dreamed about being in the position that I’m in.”

When the 24-year-old speaks, his words sound as if reined in. Each word resonates with a suppressed energy as it’s pushed down through his diaphragm, forged by thought, before it’s released into the air.

When the 24-year-old speaks, his words sound as if reined in. Each word resonates with a suppressed energy as it’s pushed down through his diaphragm, forged by thought, before it’s released into the air.

“If you passed your goal, then you’ve already made it,” said Strain. “Why worry about what everybody else thinks? Why not just do you?”

Peering from underneath the bill of a pulled down baseball cap, he turns from his computer. He asks whether or not I’ve listened to his music. Of course, there’s the feature in which he appears with D12’s Bizarre on “A Bizarre Cypher.” Then, there’s another in which he’s on with Afroman. Between the two, he’s earned nearly 2 million plays on Spotify. With a wave of his mouse, he pulls up a track from his Pro Tools catalogue. The song appears as an amalgamation of bricks on the flat screen monitor. He hits play. As a thin, dark line rakes over the bricks, music fills the room.

Everything’s got a cause

and it came with a price.

You’ve got your fame on stage,

with your name in the lights.

It ain’t a job or a hobby

how I’m able to write.

‘Cause it’s the only thing I had

to be stable in life.

Strain identifies himself as an underground rap artist. He’s emerging from within a scene the music industry has noticed in recent years. There’s a handful of artists whose time on national television has made them household names, like Sawyer Fredericks. There’s Jocelyn and Chris Arndt, and State Champs who’ve drawn the attention of Billboard and Alternative Press, respectively. There’s also Souly Had, who last February signed a record deal with Island Records.

The attention to Souly Had was not a surprise. He had long since attained eminence within the local rap scene. Strain shared a bill with him at an Upstate Concert Hall show that headlined Chris Webby.

“To be honest with you, I think he sold more tickets to the show than the actual headliner,” said Strain. “After he got off the stage, half of the crowd just left.”

Despite Souly Had’s success, the area’s rap scene is still on a short leash. You can catch it in Albany and Schenectady. Upstate Concert Hall and Skyloft in Crossgates Mall are some of the larger venues that have been friendly to the scene. A 2015 incident at a show headlining Migos at the Washington Armory led to a riot. The Armory hasn’t hosted a hip hop show since. When something happens, the leash gets pulled back.

“People that make music,” Strain said, “they tend to make music about their life.”

“People that make music,” Strain said, “they tend to make music about their life.”

Strain remembers getting his first rap CD from his mother when he was in first or second grade. His parents split up when he was young. His father’s influence won over him when it came to music. His country music-loving mother conceded that her son hated her taste in music. It was Eminem’s “The Slim Shady LP.” He fell in love with it.

“I definitely was not old enough to be listening to this,” he said. “But, my mom — thank God for my mom — gave me that CD. … I would just listen to it and maybe even music brainwashed me. It’s something that I fell in love with.”

Strain was in junior high school when he started penning rhymes. He discovered a classmate who was writing lyrics. Strain sat next to him and said he wanted to write a rap. Something funny. Though he was earning the grades to make honor roll, Strain said he’d pretend to act “stupid.” He was amazed at how easy it was to write. He wasn’t rapping, but he was counting syllables and putting words together. He didn’t think of himself as talented, but he discovered what he wanted to do. School became less important.

By the time he reached high school, Strain was getting into trouble. His mother was in Scotia. His father was in Glenville. He discovered marijuana. He’d toke up before school. He was expelled in ninth grade. The following year he got into a fight and was expelled again.

“I feel like back in the day I was the bully, almost, to people,” Strain said with a contrite tone in his voice. “I had some problems at home and maybe I took it out on other kids.”

Strain took his words one day and rattled off a rhythm in front of his computer’s webcam. It was great, he said, but it was something. He posted the video on to YouTube, and with a click of a button, debuted his rap talents to the world. In high school, that world is small, and the reaction is immediate.

Strain took his words one day and rattled off a rhythm in front of his computer’s webcam. It was great, he said, but it was something. He posted the video on to YouTube, and with a click of a button, debuted his rap talents to the world. In high school, that world is small, and the reaction is immediate.

“The whole school got it and made fun of me so bad, man,” he said. All of his transgressions as a self-confessed bully were paid back in a concentrated moment. “I got it back so hard. I deserved every bit of it.”

Strain bounced from school to school. He bookended two stints in Scotia and Burnt Hills with a stop in Mechanicville. In eleventh grade, he quit. He recalls how the school administration tried to convince him to return.

“I already knew I wasn’t going to college and I feel like even going to college is somewhat of a scam,” Strain said. “It’s like, why go to college and waste all this money? … Back then, I really wanted to do music. I wasn’t even talented at the time. This is just what I want to do. It’s how I express myself and run from my problems.”

Speaking with Strain today, he shows his business acumen for the music industry. “The best way to be a musician in this day and age is to find people who you don’t know in different states, who are obviously talented too,” he said. In the past three years, he’s paired up with Afroman, and Bizarre of D12. The latter group was Marshall Mathers’ crew from Detroit, before the rest of the world learned to know him by his stage name, Eminem.

Bizarre composed a virtual cypher, a battle of words, involving Strain (then known as WithADollarSign), and local rappers Mikey Phin and Upstates. The track starts with the crackle and buzz of a terrestrial radio station, and Bizarre as the on-air personality. He invites the listener to the cypher. The veteran on the mic starts it off. With his choice of words, he establishes his credibility before handing the mic off. It was a tired rhythm, Strain said he received back from Bizarre within an hour of approaching him. Nonetheless, the man who stood in the same crew as Eminem is still a legend in his eyes. Strain stepped up and fired his shot.

Yo, they film when I’m in the room,

Hype in the interview,

B*tch, I got sh*t to do,

Don’t get your sh*t confused.

Yeah, I make consistent moves,

I ain’t got sh*t to prove.

… my flow go through the roof.

“I thought the song turned out pretty good,” Strain said. “I didn’t think it was going to do what it did. I was not expecting it at all.” The track has earned nearly 2 million plays under Upstates on Spotify. He’s since paired up with Afroman on another feature. Strain said there were plans to bring the “Because I Got High” artist to the Capital District before the pandemic broke out. By attaching his name onto more well-known artists, he’s following a networking strategy corporate executives pay thousands of dollars to consultants to teach. He’s laid down the breadcrumbs for people to follow and find him.

“He’s on the come-up, definitely,” said Josh Mirsky. On top of fronting Mirk, he owns Foster House Studios and teaches Hip Hop Academy. He’s produced for Jay-Z, worked for major record labels and licensed tracks for a list of national television networks that includes NBC, VH1 and ESPN.

Mirsky has also served as a mentor for Strain in recent years. Their studios neighbor each other at the Armory’s top floor. “He’s really mastering social media. He puts in so much work behind the scenes.” Despite Mirsky’s connections, Strain was able to provide him something he hasn’t yet obtained. A little, blue verification mark on social media.

“My plan is that I’m going to start dropping stuff as soon as that blue checkmark hits,” said Mirsky. “I’m going to release a sing, advertise, because I think it adds a little more validity to you. People will ask, ‘Why don’t I know this guy?’ … He figured that out.”

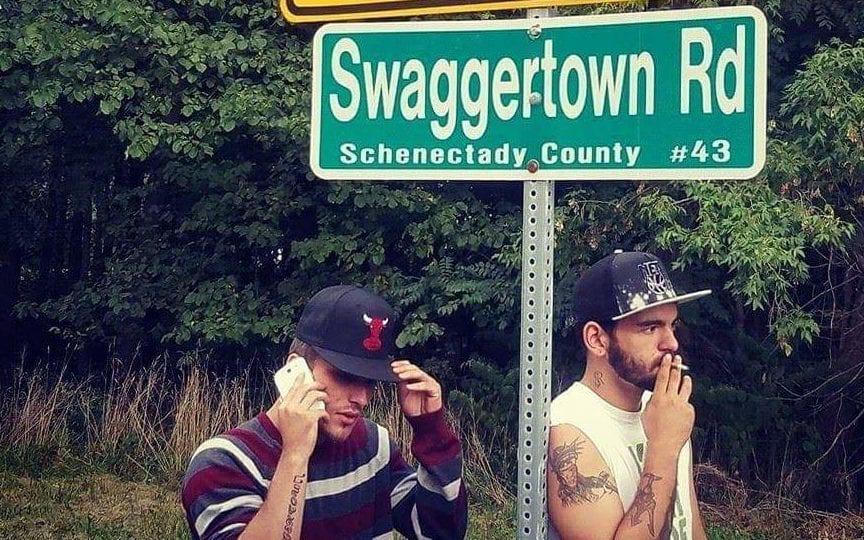

A few years ago, Strain and his friend Carl Plue decided to pose for a picture in front of a sign for Swaggertown Road. Celebrities speak of having “swag,” Strain said. “People were more worried about fashion and stuff, and I was like, ‘I live on Swaggertown Road.’”

The picture was posted on Reddit under the hashtag “trashy.” There were jokes about his tattoos. “I was reading the comments, and I was like, ‘Dude. They’re all making fun of me,’” he said. “Some of the comments were super funny. And, then it was like, ‘How do I find this kid’s music?’” Within the 600 comments that followed, many more indicated they went to Strain’s SoundCloud account to hear his music. And, they liked it. He’s kept the picture to advertise his record label, Swaggertown Records.

Strain stares back at his computer monitor as he leans back in his chair. His fingerprints are the words on each of his tracks. However, he said he knows, “the first thing about having a good song is a good beat.” The quality of the sound is paramount. Burgeoning artists often make the mistake of ripping beats straight off the streaming service, stealing it from the producer who is advertising a fee. Never paying mind to the poor sound quality and the tags embedded within the recording. “You’re really setting yourself up for failure. You could just buy the beat for $30 and you’ll have a way better sounding record.”

Though he describes his career in a “standstill,” he’s making moves to build his team up. Helping them reach their goals, earning those blue checkmarks of validation and more, to help them succeed. But, that question comes back to how one measures success.

“I got made fun of by people for making music back in the day,” Strain said. “All I wanted to do was sell a couple of tickets to the people who, I guess, hurt my feelings. To the people who really pushed my buttons.

“And I did that.”