ALBANY — With a name synonymous with the region and recognizable landmarks gracing the canvases, the Hudson River School artists remain a vital facet of American art and history. The Albany Institute of History and Art and Olana State Historic Site are working to keep the art preserved for generations to come.

In addition to the ongoing exhibition “The Hudson River School: Landscape Paintings from the Albany Institute” in the Christine and George R. Hearst III Gallery, there is a second exhibition from March to October that focuses on the work of two Hudson River School artists, William Hart (1823-1894) and his sister Julie Hart Beers (1835-1913).

The new exhibition “Hudson River School Journeys: Watercolors and Drawings by William Hart and Julie Hart Beers” will feature work by both siblings. The Institute received a substantial gift of William Hart’s work from his estate at the end of 2004. Dr. Douglas McCombs, chief curator, has recently begun working with Hart Beer’s estate, which has loaned out her work.

“I’ve been able to really bring one of the very few female artists into the spotlight. There were quite a few female artists, but they’ve been neglected over the last hundred years,” said McCombs. “More recently, curators have made an effort to return them to their proper place.”

“There were a lot of women painters and artists of color,” said Sean Sawyer, the Olana Partnership’s president. “That’s important, broadening that perspective. Interest in the American landscape was not limited to one set of society.”

As the investigation into William Hart and Julie Hart Beer’s estates continues, more information about their lives has been revealed. According to newspaper reports, Julie taught other female artists. She frequently took her female students on sketching trips into the Hudson Valley’s untouched forests and fields.

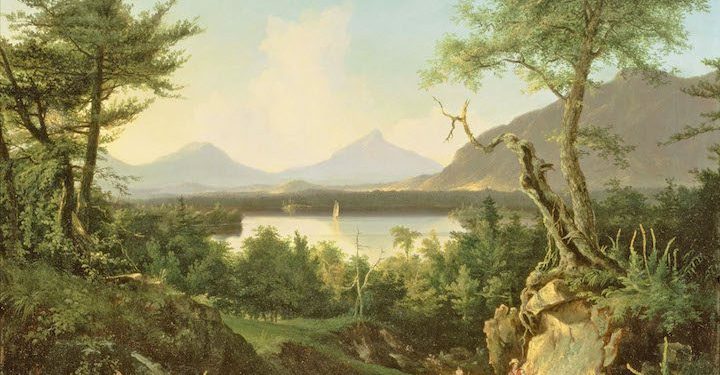

The artists who painted in the style now known as the Hudson River School movement lived all over the country. It has been noted that the artists were among the first environmentalists.

According to Sawyer, their paintings “spoke to bigger ideas and captured the essence of what they were seeing.”

One of the most famous painters from the era is Frederic Church. Church, a student of fellow artist Thomas Cole, is known for his large paintings that strike a balance between the scientific and the divine.

Church’s Olana estate is another manifestation of his care for nature. Documents at Olana demonstrate his desire to plant as many trees as possible while preserving the acres around him.

“That was so much a part of it, being out in this landscape in the Hudson River valley and the Catskills,” said Sawyer, “looking and endlessly drawing and painting to capture the beauty of the area.”

“During the mid-19th century, artists were really turning to the landscape,” noted McCombs. “I think it’s so important for us today and so much a part of our culture, because it reflects what those artists were seeing as a part of the American character.”

The artistic interpretations of the American landscape are believed to have represented the ideals of freedom, liberty, and independence.

“Today, people debate that, but at the time it was a part of our cultural identity,” said McCombs.

“The idea of these expansive tracks of land and wilderness and forested areas is something that still identifies America today, even though we’ve lost much of it over the years,” he continued.

Painters from all over the country painted in this style, drawing inspiration from locations other than the Hudson River, including the Rocky Mountains, Antarctica, Maine and Ohio. However, the Hudson River provided unique symbolism.

“The Hudson River was a central part of their lives,” said Sawyer.

The Hudson River was a famous landmark of the era, appearing in numerous songs and works of art.

Sawyer said it was “an expression of love for American landscape and landscape painting.”

This style of landscape painting fell out of favor as the newer French Impressionism style gained traction. A critic coined the term “Hudson River School” near the end of its era and used it derogatorily.

The movement has seen a resurgence of popularity with tourists, art lovers and researchers over the years, due in large part to the efforts of dedicated art historians in the 1970s.

From May to October, a new exhibit called “Terraforming: Olana’s Historic Photography Collection Unearthed” will be on display at Olana. The exhibit will center on Olana’s photographic history.

“Some of the 5,000 historic 19th century photographs that Church collected have never been seen by the public,” said Sawyer. “They’re these remarkable photographs by almost all of the biggest names in photography. It’s one of the hidden treasures of Olana.”

Next winter, Olana will focus on one of Church’s most famous works, “The Heart of the Andes,” bringing the exhibition at the Smithsonian to Olana.

With its ongoing and temporary exhibitions, the Albany Institute is preserving the legacy of the Hudson River School and its artists. Douglas McCombs has been collaborating with the family of artist Susie M. Barstow to expand the Institute’s resources on her work.

One hundred watercolors were donated by a relative of Barstow.

“It’s an amazing addition to our collection,” McCombs said.

“I think a lot more curators, writers, and students are finding interest in the artwork of the Hudson River School period,” said Sean Sawyer. “It was such a formative period for our country and the world. The art that was being produced is an important document to understand history.”

The Albany Institute of History and Art is located at 125 Washington Ave., Albany. Learn more at www.albanyinstitute.org. The Olana State Historic Site is in Hudson, N.Y. For more information or to plan a visit, go to www.olana.org.