Before New York Times best-selling author Gary Vaynerchuk inspired would-be entrepreneurs into action through LinkedIn, he was a sports fan.

Vaynerchuk has a near cult following of disgruntled professionals seeking the gumption to jump-start a new career or perhaps find the next, big trend into which to invest. Which is why it’s sometimes jarring to hear him pitch sports cards as the next investment.

I’m old enough to remember the last baseball card boom. Young professionals with expendable income turned to card conventions and tried to reclaim the collection their mothers threw out. As they started throwing hundreds of dollars for every Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays, the consciousness of the hobby spun from collectible to investment opportunity. By the ‘90s, card companies played into the supply-and-demand game. The price of cards over the counter went from cents to dollars.

Truth is, sports card collecting never went away. Vaynerchuk may be the loudest voice in the room, but there are plenty of hobbyists who’ve been saying it for years; it’s just not as mainstream as it once was, and that’s partially due to the internet. Buying and selling still happens in hobby stores around town, but the bulk of it takes place on eBay.

Gone are the days of conventions at the Polish Community Center. Those events garnered hundreds of vendors, sports fans, and the occasional Hall of Famer. The casual collector is somewhat of a dinosaur, maybe. If so, I’m that dinosaur.

My collection stays with me, and I have little intent on selling anything from it. To do so would mean assessing its value. I’d have to submit it to a grading service, and I have little interest in that. Besides, I’m still collecting.

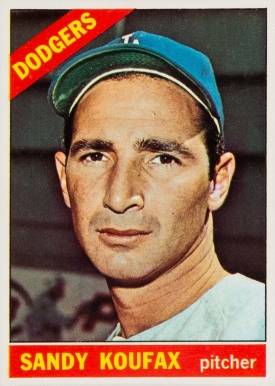

I’m not an investor. Afterall, my buying strategy is still influenced by a 35-year-old baseball simulator I played on a Commodore 64. Whenever I pick up a card, the act of turning it over to read the statistics is ingrained in me. It could be a Sandy Koufax or a Warren Sphan, both are good players — they’re in the Hall of Fame. I just need to see how he performed the year before.

My love for baseball grew beyond the patch of green grass at school. My friends and I first started playing dice baseball. We’d field a team after buying a few packs of cards. Sometimes someone had to play out of position. The game was rudimentary: one six-sided die determined if a hitter singled, doubled, tripled, homered, struckout or walked. Not a pitcher went unscathed. When Micro League Baseball came out with the ability to create teams, we evolved our game to the modern age.

One weekend, my friend and I had our own winter meeting. I brought my baseball cards over to his house and we conducted a draft. We could only draft players we had in our collection. Furthermore, we could only use the statistics from the previous year. You could draft George Brett, but unless you had his card from 1981, you couldn’t use his .390 batting average. We drafted enough players to field 15 teams, each — 750 players, total. It was a long weekend. Free agent pickups followed. After hitting a convention, one of us would phone the other: “I choose Roberto Clemente,” or “I’ve got Mickey Mantle.”

In a similar vein to the baby boomers of the ‘80s, I find myself shopping baseball cards online. I’m not looking for jewelry-grade cards. My wife would kill me. The cards I find may have likely spent time in the spokes of a bicycle. The brutal appearance of one Ted Williams card only suggests it was once owned by a Yankee fan. That’s the kind of story a mint condition card doesn’t have.

On my computer, I have a Commodore 64 emulator. With it, I have a copy of Micro League Baseball and so many more “disks” to compliment it, including the one that allows me to create my own teams. Unlike when I was a kid, I now find it difficult to read the statistics on the back of cards. Still, I’m back in the habit of finding the next free agent.

Hey, Gary. I’ve got a 1966 Sandy Koufax.