VOORHEESVILLE — Andrew Ward, the village public library’s digital services librarian, delicately unearthed a petite beige and worn-out diary from the library’s archives boxes. Placing it on the cold, grey table, it appeared unassuming and modest but its cover alone already indicated why it’s been safely kept in storage.

Titled “Latent Self Closing Diary for 1871,” the diarist’s identity was not jotted down although the library believed it belonged to a New Scotland farmer at the time named Derrick Van Schaick Raynsford, based on its contents. The diary contained numerous pages of handwritten notes and numerical calculations which Ward assumed that “it was keeping a notation of the money he had, what he bought and sold, and it pretty much showed what a day-in-day-out life was like in the area.” Ward observed that much of the diary dealt with his farm work, what products he sold in Albany like veal and pork, when he attended funerals throughout the year, and mentions of enjoying county fairs.

From its contents, Ward learned that Raynsford grew hay, potatoes and carrots; owned an apple and pear orchard; had at least two farm workers, one of whom was his son, Albert; he and his crew worked on Christmas Day; and he attended the Reformed Church in Guilderland Center and the New Scotland Presbyterian Church. The diary also included an 1871 calendar which noted the moon’s phases, when the moon rose, and the times the sun would rise and set — this was all organized in a tightly-organized serif typeface.

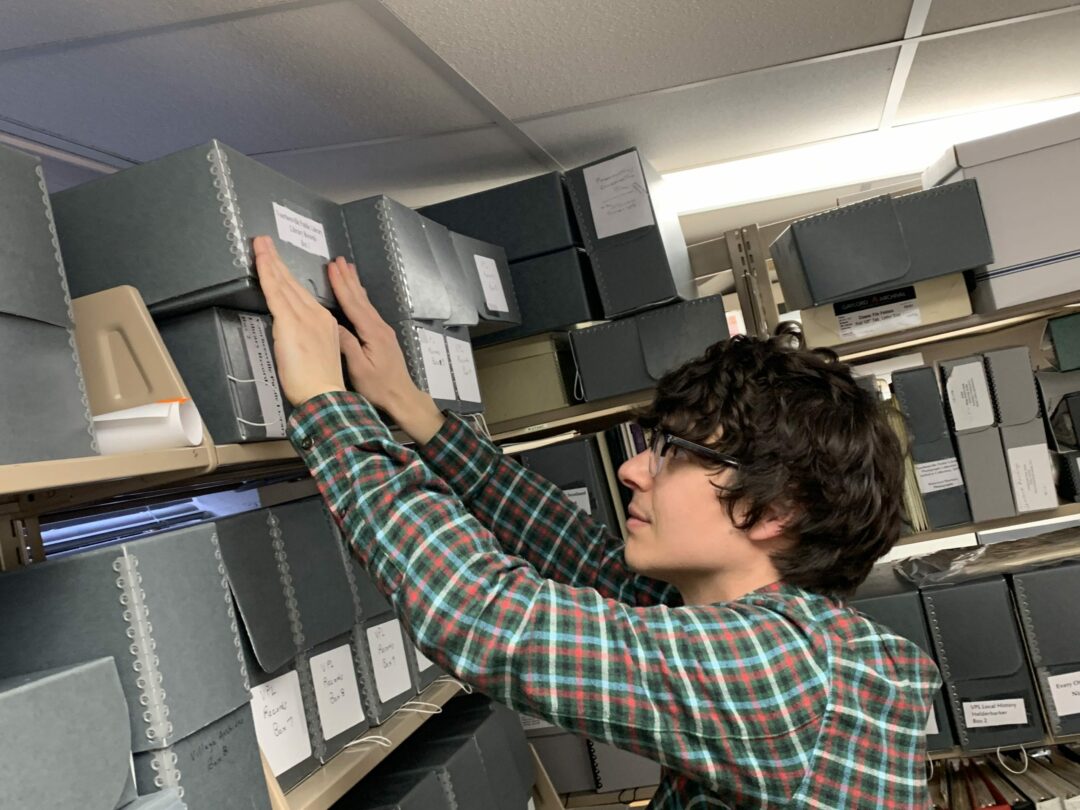

Once Ward gently returned the fragile diary into its folder and box, he returned it to the library’s archives which he said comprised of at least 130 boxes of collected historical photographs, documents, postcards, yearbooks, letters, business records, church and family history, receipts and more. These items were mainly focused on Voorheesville and New Scotland’s past, and mostly dated from the 1920s to 1990s.

Ward mentioned that the aforementioned 1871 diary and a photograph of a Civil War-era soldier are probably the library’s oldest collected items. He also noted how the Voorheesville railroad station and trains passing by were among the most documented items in the library’s archives, including an old photograph of engineers standing in front of a train, one of a train crash, and one that emphasized the railroads themselves.

“We have a lot of documented information about the trains because they were so central to the village, and we also learned that many people were hit by trains in the first half of the 20th century,” he said. “This is a very rural area so people and even animals did not realize when there was an incoming train and it became a big thing to properly put up warning signals and lights for crossing.”

While these items have been safely stored here, the library has begun digitizing them since 2015 in order to make them more accessible to the public who may want to view it out of curiosity, for research or to reminisce about the past.

Ward said a program called New York Heritage was developed then which works with many statewide libraries to have digitized collections of photographs, documents, maps and more, to give people easy access to them for free. The New York Heritage is a combination of seven Empire State Library Network members, one of which is the Capital District Library Council which oversees the Voorheesville library. “I think that having free access in a searchable, indexable way online is great and that’s how digitization helps us,” he said. “With younger generations, quickly looking up items is what they can expect.”

Ward explained the digitization process: placing the historical item on a flatbed scanner to develop high-resolution scans, crop the file and/or make any needed color corrections, preserve the master digital file, transfer it into a JPG file and put them in a reasonable resolution for people to view.

For now, the library has only the flatbed scanner for the process but Ward said it may not always be the ideal digitization mode, especially when handling more three-dimensional items like books, diaries and even an old Smith Tavern’s cup. “You obviously shouldn’t take a book and put it on a flatbed scanner because you could damage its spine, unless there are loose individual pages to scan easily,” he said. “What I could do is instead maybe place the book on a table and have a camera on a tripod above that’s far enough to take a picture of one page. Then, I can crop it and manipulate it for a digital scan.”

Although Ward said the current flatbed scanner gets the job mostly done for now, he said it is slow — he could not recall how old the scanner is — and it wouldn’t hurt to get a new and faster scanner perhaps one day. “It’s something that I’ve definitely thought about,” he said.

Regardless, he said that while the library is “nowhere near close to being done with scanning all the two-dimensional items,” people interested in accessing the physical archives should make an appointment with the library — he warned that not every librarian here is equipped to handle the archived materials though — and he would be able to present items to them. People would need to fill out some forms first so that the library can record who has been accessing the archives and upon arrival, Ward would be able to help them out.

“I would just remind people that these are our history and they could make the most out of them if they want to learn about their past or the village’s history, if they find it interesting,” he said. “It’s partially why the library safely keeps them and why I do what I do here.”

Reflecting back on the 1871 diary, Ward brought up how the writer most likely did not realize that his diary would become important decades later to showcase what local everyday life in 1871 was like, which is another reason why the library continues to digitize its archives.

“These things are irreplaceable and although they might not be copies of the Gideon Bible or the Magna Carta, they’re things that we have very little knowledge about and we’re certainly not taught about the history of everyday life then,” he concluded. “We also don’t really get to learn what everyday people thought in various periods of history, so it’s stuff that will get lost if we forget or don’t care about it.”

Photos by Diego Cagara / Spotlight News